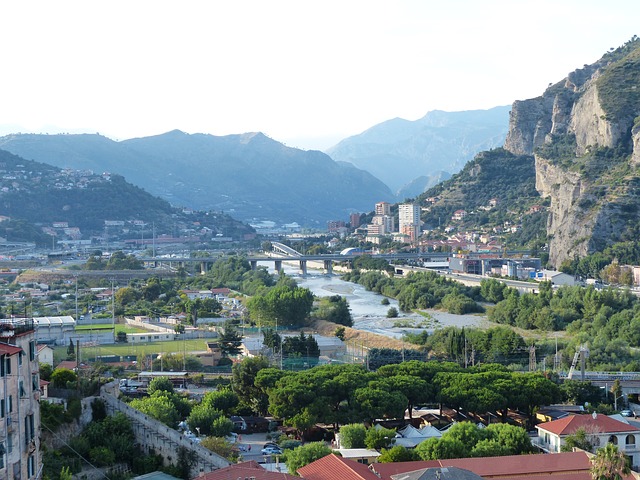

Ventimiglia is a “gate,” not a “border” – at least as long as France does not suspend the agreements in place that allow people to come and go. So it has become a funnel for migrants who consider Italy a stepping stone to reach destinations beyond the border.

Ventimiglia is a “gate,” not a “border” – at least as long as France does not suspend the agreements in place that allow people to come and go. So it has become a funnel for migrants who consider Italy a stepping stone to reach destinations beyond the border.

“In the past year, more than 20,000 people have come through Ventimiglia,” says Paola, a member of the local Focolare community. “It’s like adding another Ventimiglia, since our population is around 24,000 inhabitants.”

A teacher at the diocesan seminary, she recalls how “between February and March 2015, the seminarians started to distribute food to the homeless at the station. As days went by, however, the homeless started to multiply.”

They were seeing migrants who, after landing on the Italian coast, aimed to cross the border with France and reach other European countries.

“That’s when the ‘emergency’ began, and it has not let up since. At the beginning we joined other locals to volunteer and distribute sandwiches on the street.” Collaborating with Caritas, “we contacted the Focolare community on the other side of the border, and they took turns with us, supporting us with money collected from fundraising during Monaco’s Grand Prix.

“In June 2015,” she continues, “a Red Cross camp sprung up near the station. Access was limited, but a number of us could enter under HACCP and collaborate in a number of ways.”

Alongside this “official” camp was another more “informal” one, right on the border with France. “Many immigrants had no documents, and seeing that the camp organized by the Red Cross required identification, many preferred staying there and trying to cross the border as fast as they could.” Then, at the beginning of October, the camp was dismantled and cleared out in a “pretty rough way.”

“When the Red Cross camp was closed in May 2016, we suddenly found ourselves with more than a thousand people in town. It was an unsustainable situation, worsened by a local law that prohibits distributing food and essential goods to immigrants, which carries penalties and tickets.

“Then Caritas intervened to mediate. That’s how we started welcoming people at the Church of Sant’Antonio. By day it was a church; by night, a dormitory. Families with children and the most vulnerable were hosted in the church – the pews were moved and we brought covers, and then in the morning we would clean it all up.”

In July 2016 a new Red Cross camp was opened outside the city for men. Women and children continued to be hosted in church.

In July 2016 a new Red Cross camp was opened outside the city for men. Women and children continued to be hosted in church.

“In 2017 a seemingly infinite influx of minors began, and most of them stayed along the Roya River. The local prefect asked the Red Cross to open up a section of the camp for them.

“In the meantime, there were continual sweeps, with hundreds of immigrants boarded on to buses for Taranto in Southern Italy. Yet just days later they were back again. “The fact is,” she explains, “that these people want to reconnect with relatives in other countries, and this is why they are ready to do anything. It’s from here that they can try to cross the border. There are some who have tried ten times before succeeding.” The border is guarded day and night.

“Unfortunately, all we are doing is fostering dependency. But they don’t need clothes or a pair of shoes. They need to exercise their freedom of self-determination, which every person should have.”

Perhaps the solution could be to create a transit camp, Paola suggests, “a place where an immigrant, during the journey, can stop, find nourishment, wash, change clothes – where they can receive medical attention and legal assistance they need.”

Paola calls their service “nothing at all,” but it is these details that help these travelers feel like people again.

“We cook African or Arab recipes based on couscous and rice, which we learned how to mix with spices and create dishes according to their traditions.

“One day we noticed that a Syrian woman bathed herself each time she came to Caritas, yet she kept putting on the same outfit. She was wearing a tunic with pants. She kept reaching into the piles of clothes, but each time she went away empty handed.

“Then we understood and asked some friends from Morocco if they had some clothes in her style. Finally, she was able to change and went away happy.”

Source: United World Project

Italiano

Italiano Español

Español Français

Français Português

Português

No comment