Cameroon: Christianity and the Bangwa Culture

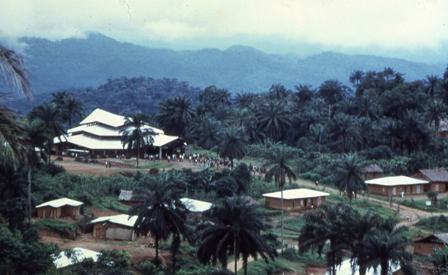

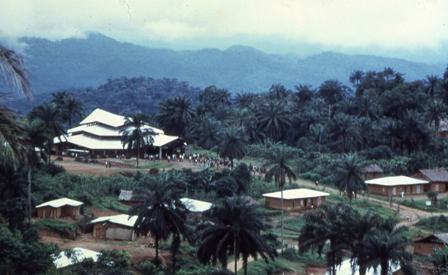

“I was asked to present a report on the Christian witness in front of African tradition. It wasn’t easy for me, for two simple reasons: the first is that I am a Bangwa, the second is that I’m not only Christian, but also the bishop of Mamfe.” The speaker is Bishop Andrew Fuanya Nkea at a symposium on dalogue between traditional African religions and Christianity, during the 50th anniversary celebration of the Focolare Movement in Fontem. Fifty-one years old, he is originally from Widikum, Cameroon, graduate in Philosophy and Theology, a priest since 1992, pastor, secretary of the Diocese, professor and formator, Secretary General of the Catholic University of Cameroon and recently named Bishop of the diocese of Mamfe. “I decided to use a more practical than theoretical approach in my talk,” said the bishop who then proceeded to recount the history of the relationship between the Bangwa culture – especially in the south west region of Cameroon, the Lebialem District – and Christianity. That relationship was marked by an encounter that turned into a sort of parting of the waters between a before and an after: the encounter with the Focolare Movement. Bishop Andrew Fuanya is a living demonstration that it is possible to overcome the dualism between two traditions, without falling into religous syncretism. The Christianity brought by the first missionaries who arrived in Cameroon in the 1920s had placed the population in front of a fork in the road: “Either you become Christian and avoid all aspects of the traditional religions, or you practice the Bangwa religion, remaining a pagan, good only as firewood for hell.” There was little or no dialogue between Christianity and the local culture. Typical musical instruments were banned in church, along with traditional prayers. In spite of the rigidity and inflexible methods used by the first missionaries, many people embraced Christianity, even though it was very difficult and in direct opposition to their communities.

“I was asked to present a report on the Christian witness in front of African tradition. It wasn’t easy for me, for two simple reasons: the first is that I am a Bangwa, the second is that I’m not only Christian, but also the bishop of Mamfe.” The speaker is Bishop Andrew Fuanya Nkea at a symposium on dalogue between traditional African religions and Christianity, during the 50th anniversary celebration of the Focolare Movement in Fontem. Fifty-one years old, he is originally from Widikum, Cameroon, graduate in Philosophy and Theology, a priest since 1992, pastor, secretary of the Diocese, professor and formator, Secretary General of the Catholic University of Cameroon and recently named Bishop of the diocese of Mamfe. “I decided to use a more practical than theoretical approach in my talk,” said the bishop who then proceeded to recount the history of the relationship between the Bangwa culture – especially in the south west region of Cameroon, the Lebialem District – and Christianity. That relationship was marked by an encounter that turned into a sort of parting of the waters between a before and an after: the encounter with the Focolare Movement. Bishop Andrew Fuanya is a living demonstration that it is possible to overcome the dualism between two traditions, without falling into religous syncretism. The Christianity brought by the first missionaries who arrived in Cameroon in the 1920s had placed the population in front of a fork in the road: “Either you become Christian and avoid all aspects of the traditional religions, or you practice the Bangwa religion, remaining a pagan, good only as firewood for hell.” There was little or no dialogue between Christianity and the local culture. Typical musical instruments were banned in church, along with traditional prayers. In spite of the rigidity and inflexible methods used by the first missionaries, many people embraced Christianity, even though it was very difficult and in direct opposition to their communities.  The novelty represented by the first visit of Chiara Lubich to the royal palace of the Fon of Fontem in 1966 can be described with an image used by the Focolare foundress in describing the first spark, the first inspiration of the interreligious dialogue that would later develop: “Suddenly I had the strong impression of God as an enormous sun that embraced everybody with His love – us and them.” A new era had begun, driven on the wind of the Second Vatican Council and by the extraordinary story of the friendship among the first focolarini to reach the spot and the Bangwa people. The focolarini included doctors who had come to wipe out the sleeping sickness that was decimating the population. Since then, the relationship between the faithful of the two religions have been characterized by deep mutual respect which restored dignity to the traditional culture and was a veritable laboratory in which the identity of both religions could grow. The bishop explains: some local religious traditions were kept, such as praying to the dead, so that they might intercede for the family, or the Cry Die, the day dedicated to them; other things were strange to their new faith, such as polygamy, animal sacrifice and witchcraft. The new inculturation, concluded the bishop, according to the spirit of the Second Vatican Council, does not come from an imposition of a rigid uniformity, but is inspired by the values of dialogue and collaboration, in the search for the ‘Seeds of the Word’ that are scattered in every religious tradition. “The challenge for the Christians of Lebialem for the next 50 years will be to recognize that their credibility will depend on how much they are able to love everybody, independant of the religion they belong to.” Only in this way will they be authentic Christians and authentic Africans.” Chiara Favotti Full interview with Mons. Andrew F. Nkea

The novelty represented by the first visit of Chiara Lubich to the royal palace of the Fon of Fontem in 1966 can be described with an image used by the Focolare foundress in describing the first spark, the first inspiration of the interreligious dialogue that would later develop: “Suddenly I had the strong impression of God as an enormous sun that embraced everybody with His love – us and them.” A new era had begun, driven on the wind of the Second Vatican Council and by the extraordinary story of the friendship among the first focolarini to reach the spot and the Bangwa people. The focolarini included doctors who had come to wipe out the sleeping sickness that was decimating the population. Since then, the relationship between the faithful of the two religions have been characterized by deep mutual respect which restored dignity to the traditional culture and was a veritable laboratory in which the identity of both religions could grow. The bishop explains: some local religious traditions were kept, such as praying to the dead, so that they might intercede for the family, or the Cry Die, the day dedicated to them; other things were strange to their new faith, such as polygamy, animal sacrifice and witchcraft. The new inculturation, concluded the bishop, according to the spirit of the Second Vatican Council, does not come from an imposition of a rigid uniformity, but is inspired by the values of dialogue and collaboration, in the search for the ‘Seeds of the Word’ that are scattered in every religious tradition. “The challenge for the Christians of Lebialem for the next 50 years will be to recognize that their credibility will depend on how much they are able to love everybody, independant of the religion they belong to.” Only in this way will they be authentic Christians and authentic Africans.” Chiara Favotti Full interview with Mons. Andrew F. Nkea