Dilexi te, “ti ho amato” (Ap 3,9) è la dichiarazione d’amore che il Signore fa a una comunità cristiana che, a differenza di altre, non aveva alcuna risorsa, particolarmente disprezzata e esposta alla violenza ed è, al contempo, la citazione che dà il titolo alla prima Esortazione apostolica di Papa Leone XIV, firmata il 4 ottobre, festa del Santo d’Assisi. Il documento rimanda al tema approfondito da Papa Francesco nell’Enciclica Dilexit nos sull’amore divino e umano del Cuore di Cristo ed è un progetto che l’attuale Pontefice ha fatto suo, condividendo con il Predecessore il desiderio di far comprendere e conoscere il vincolo tra quella che è la nostra fede e il servizio ai vulnerabili; il legame indissolubile tra l’amore di Cristo e la sua chiamata a farci vicini ai poveri.

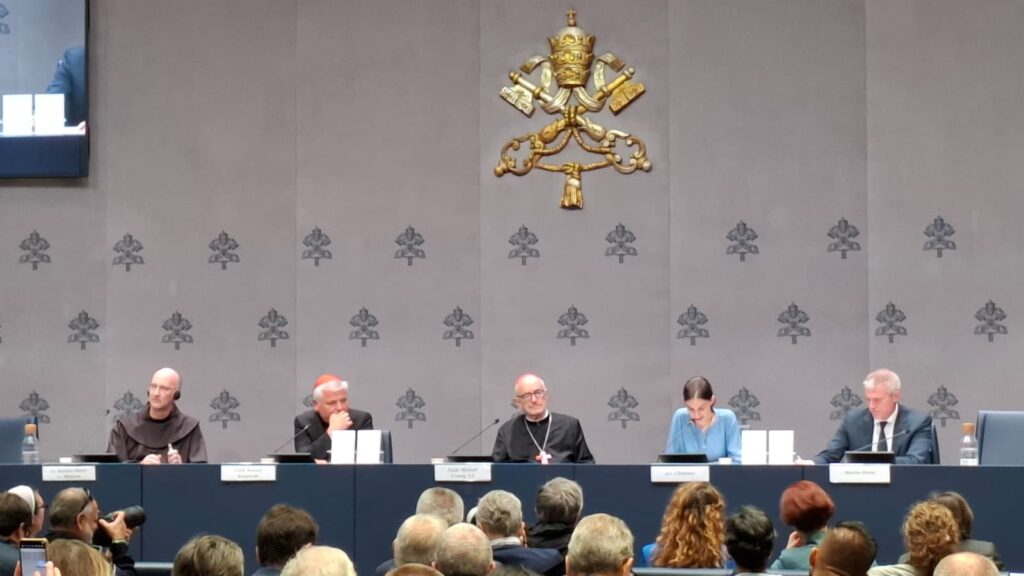

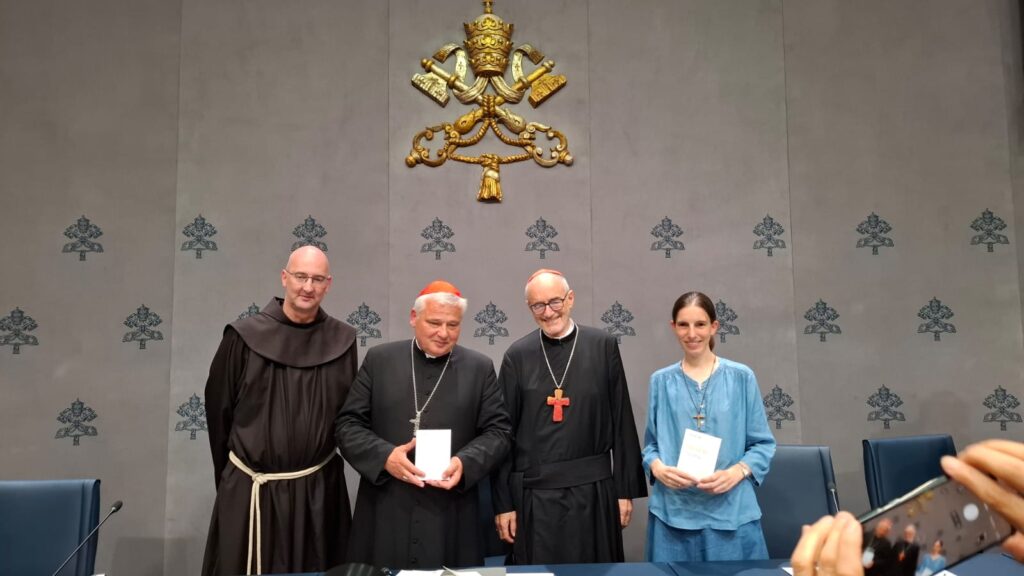

Alla conferenza stampa di presentazione della “Dilexi te” sono intervenuti (da sinistra): Fr. Frédéric-Marie Le Méhauté, Provinciale dei Frati Minori di Francia/Belgio, dottore in teologia; Em.mo Card. Konrad Krajewski, Prefetto del Dicastero per il Servizio della Carità; Em.mo Card. Michael Czerny S.J., Prefetto del Dicastero per il Servizio dello Sviluppo Umano Integrale; p.s. Clémence, Piccola Sorella di Gesù della Fraternità delle Tre Fontane di Roma (Italia).

The 121 points of the text show that being aware of the “experience” of poverty goes far beyond philanthropy. The Augustinian Pope affirms, “This is not a matter of mere human kindness but a revelation: contact with those who are lowly and powerless is a fundamental way of encountering the Lord of history. In the poor, he continues to speak to us.” (5)

Leo XIV invites us to reflect on the many faces of poverty: that of “those who lack material means of subsistence”, of “those who are socially marginalized”; “moral”, “spiritual” and “cultural” poverty; the poverty “of those who have no rights, no space, no freedom” (9). But no poor person, he continues, is “there by chance or by blind and cruel fate” (14), love for the poor “is the evangelical hallmark of a Church faithful to the heart of God” (103).

Prof. Luigino Bruni, economist and historian of economic thought, Professor of Political Economy at Lumsa University (Rome) and scientific director of the

In particular, the document denounces the lack of equality, defining it as the root of social ills (94), as well as the actions of unjust political-economic systems. The dignity of every human person must be respected today, not tomorrow (92) and, not surprisingly, during the press conference, held in the Vatican on 9th October, Card. Michael Czerny S.J., Prefect of the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development, reflected extensively on what are called the ‘structures of sin’: “selfishness and indifference are consolidated in economic and cultural systems. The economy that kills (3) measures human worth in terms of productivity, consumption and profit. This dominant mind-set ’makes the rejection of the weak and unproductive acceptable and therefore deserves the label of ‘social sin ’”.

Prof. Bruni continues, “This is an old theme of the Church’s social doctrine – – and, even earlier, of the Fathers of the Church and of many social charisms, not least the Franciscans. In these passages you can intuit the hand of Pope Francis and the spirit of Saint Francis (64), but also of the most recent charisms, it was Don Oreste Benzi who first spoke of the “structures of sin”, up to the Economy of Communion and the Economy of Francis. The reference to meritocracy, again in full continuity with Pope Francis, is also important. It is defined as a “false vision” (14). Meritocracy is a false vision, because first it attributes many forms of poverty to the poor’s own lack of merit and then labels those same ‘unworthy poor’ as guilty. Meritocratic ideology is one of the main “structures of sin” (nos. 90 et seq.) that generate exclusion and then try to justify it ethically. The structures of sin are material (institutions, laws …) and immaterial such as ideas and ideologies”.

The document naturally takes a look at the theme of migration. Robert Prevost makes his own the famous “four verbs” of Pope Francis: welcome, protect, promote and integrate, not forgetting women, among the first victims of violence and exclusion. He stresses the importance of education for the promotion of integral human development, highlights the witness and link with the “poverty” of many saints, blesseds and religious orders and proposes a return to almsgiving as a way to truly touch “the suffering flesh of the poor” (119).

In Dilexi te Pope Leo “urges” us to change course, to think of the poor not as a problem of society nor merely as “the objects of our compassion” (79) but as real actors to whom we can give voice and as “teachers of the Gospel”. We need to let ourselves be evangelized by the poor. The Pope writes, “the are part of our family”. They are “one of us”, therefore, “our relationship to the poor cannot be reduced to merely another ecclesial activity or function” (104).

Luigino Bruni adds, “To take evangelical poverty seriously means changing our point of view, in the deeply transformative way, the metanoia of the first Christians. And then, today, trying to answer some radical questions: how can we call the poor “blessed” when we see them as victims of misery, abused by the powerful, dying at sea, searching for food in our waste? What beatitude do they know? For this reason, the first and most severe critics of this first beatitude have often been and still are, those who spend their lives next to the poor, sitting with them, seeking to free them from their misery. The greatest friends of the poor often end up, paradoxically, becoming the greatest enemies of the first beatitude. We must try to understand them and thank them for being scandalized. And then try to advance the discourse into new and daring terrains which are always paradoxical. And how many “rich gluttons” have found in the beatitude of the poor an alibi to leave Lazarus (ref. Luke 16:19 -31) ‘blessed’ in his condition of deprivation and misery, perhaps even calling themselves “poor in spirit” because they gave some crumbs to the poor! There must be something wonderful in that “blessed are the poor”. We don’t understand it but at least let’s not reduce its paradoxical and mysterious prophecy.

Pope Leo has tried to indicate some dimensions of this paradoxical beauty of poverty, especially in the long paragraphs dedicated to its biblical and evangelical foundation, but there is still much to discover and to say. I hope that future papal documents will also include the secular magisterium on poverty, which for at least 50 years has been given to us by people such as Amartya Sen, Muhammed Yunus and Ester Duflo, laureates of the Nobel Economics Prize. These and many other scholars have taught us that poverty is not a lack of money or income (flows) but a lack of capital (stocks): health, education, social, family, capabilities which later manifests as low income. It is only by working on these forms of capital today can we help the poor escape the poverty traps tomorrow. As Sen explained to us, poverty is the objective impossibility “to lead the life we would like to live” and is therefore a lack of freedom. Charisms have always intuited this, in missions, in Europe and everywhere, they filled the world with schools and hospitals, to improve the ‘capital’ of the poor. Even almsgiving, of which Pope Leo speaks at the end of the document (nos. 76 et seq.), should be directed towards ‘capital accounts’ and not dispersed in monetary aid that often increases the very poverty it intends to reduce.

The Dilexi te is a starting point, for a long journey still ahead for Christians in the still partly unknown terrain of poverty, both the ugly kind to be reduced and the beautiful Gospel kind to be multiplied.

Maria Grazia Berretta

0 Comments