Nov 14, 2020 | Non categorizzato

Open to all, a Webinar promoted by the Pontifical Commission for Latin America to reflect and analyse the impact and consequences of COVID-19. The social, economic and political implications along with the thought of Pope Francis.  The virtual seminar entitled Latin America: Church, Pope Francis and the pandemic scenario will take place on November 19th and 20th 2020 and will be open to all those interested in this part of the world, which is also heavily affected by the virus; a situation already problematic due to many areas of poverty and marginalisation. The event aims to reflect on and analyse the pandemic situation on the Latin American continent, its consequences and, above all, the proposals of action and of aid from governments and from the Church. It is organised by the Pontifical Commission for Latin America, the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences and by the Latin American Episcopal Conference (CELAM), The Pope will contribute with a video-message. Contributions will also be made by Card. Marc Ouellet, President of the Pontifical Commission for Latin America, Mgr Miguel Cabrejos Vidarte, President of CELAM, Carlos Afonso Nobre, Nobel Peace Prize winner in 2007, the economist Jeffrey D. Sachs, Director of the entre for Sustainable Development at Columbia University and Gustavo Beliz, Secretary for Strategic Affairs of the Argentinean Presidency. The introductory note to the seminar explains that to date, on the Latin American continent, as in the rest of the world, it is impossible to calculate the damage of the pandemic: “In many cases, the negative effects of border closures and the consequent social and economic repercussions were only the beginning of a spiral of damage not yet quantified, and even less a medium-term solution”. For this reason, the seminar will be an opportunity for the missionary and pastoral work of the Catholic Church and the contribution of various specialists from the world of economics and politics to meet and dialogue in order to strengthen a cultural and operational network and thus ensure a better future for the continent. Pope Francis will also participate at the presentation of the Task Force against Covid-19, established by him and represented at the seminar by its head who will present the work of the Task Force. In times of uncertainty and lack of future, the Church looks to the “continent of hope” and seeks shared instruments that can transform the crisis into opportunities or at least find a way out. For the programme of the event sign in here

The virtual seminar entitled Latin America: Church, Pope Francis and the pandemic scenario will take place on November 19th and 20th 2020 and will be open to all those interested in this part of the world, which is also heavily affected by the virus; a situation already problematic due to many areas of poverty and marginalisation. The event aims to reflect on and analyse the pandemic situation on the Latin American continent, its consequences and, above all, the proposals of action and of aid from governments and from the Church. It is organised by the Pontifical Commission for Latin America, the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences and by the Latin American Episcopal Conference (CELAM), The Pope will contribute with a video-message. Contributions will also be made by Card. Marc Ouellet, President of the Pontifical Commission for Latin America, Mgr Miguel Cabrejos Vidarte, President of CELAM, Carlos Afonso Nobre, Nobel Peace Prize winner in 2007, the economist Jeffrey D. Sachs, Director of the entre for Sustainable Development at Columbia University and Gustavo Beliz, Secretary for Strategic Affairs of the Argentinean Presidency. The introductory note to the seminar explains that to date, on the Latin American continent, as in the rest of the world, it is impossible to calculate the damage of the pandemic: “In many cases, the negative effects of border closures and the consequent social and economic repercussions were only the beginning of a spiral of damage not yet quantified, and even less a medium-term solution”. For this reason, the seminar will be an opportunity for the missionary and pastoral work of the Catholic Church and the contribution of various specialists from the world of economics and politics to meet and dialogue in order to strengthen a cultural and operational network and thus ensure a better future for the continent. Pope Francis will also participate at the presentation of the Task Force against Covid-19, established by him and represented at the seminar by its head who will present the work of the Task Force. In times of uncertainty and lack of future, the Church looks to the “continent of hope” and seeks shared instruments that can transform the crisis into opportunities or at least find a way out. For the programme of the event sign in here

Stefania Tanesini

Nov 13, 2020 | Non categorizzato

The Global Compact on Education, suggested by Pope Francis, invites all people to adhere to a Pact. This was discussed this with Silvia Cataldi, a sociologist and professor, who lectures at La Sapienza University, Rome.  The protagonists are the ones who hope in a world of more justice, solidarity and peace. The Global Compact on Education, suggested by Pope Francis, speaks of youth as being, at the same time, both beneficiaries and agents in the field of education. Together with their “families, communities, schools, universities, institutions, religions and government” they are called “to subscribe to a global pact on education” and to commit themselves to a more fraternal and peaceful humanity. This was discussed during the meeting entitled “Together to look beyond”, held at the Pontifical Lateran University, in Rome on October 15. In a video message, the Holy Father urged all people of good will to adhere to the Pact. Silvia Cataldi, sociologist and professor at La Sapienza University in Rome commented on the Pope’s words In recent years we have noticed the youth’s sturdy protagonism where important current affairs are concerned. The educational model that sees them as passive subjects seems to be obsolete… “Often, educational models limit themselves to think of culture as a concept. The pedagogist Paulo Freire speaks of the “banking model of education”, where knowledge can be poured or deposited as if in a container. However, this knowledge has two risks: that of remaining abstract and detached from life, and that of assuming a hierarchical vision of knowledge. With respect to this, the Pact strikes me as an educator, because it invites us to listen to the cry of the younger generations, to let ourselves be questioned by their questions. We must realize that education is a participatory path, and not a unidirectional one”. So, what does to educate mean? “The term culture stems from colere and it means to cultivate, a verb which indicates that one needs to dedicate time and space, by starting from questions and not from providing answers. But it also means to take care, to love. This is why I am so impressed by the Pact, because it strongly affirms that “education is above all a matter of love”. When we speak of love we think of the heart, of feelings. But love has an eminently practical dimension, it requires hands. So, we educators do our work only if we manage to understand that education is care. Daily care is revolutionary because it is an element of criticism and of transformation of the world. Hannah Arendt explains this well when she says that “Education decides whether we love the world enough because it leads to its transformation”. How can we make sure that the Pact does not remain just an appeal? The call to universal brotherhood – the core of the Pact – has important implications, but to have a transforming power it must promote a change of perspective that leads one to welcome diversity and heal inequalities. The French sociologist Alain Caillé says that “fraternity is plural”, and this means that if in the past brotherhood was only among peers, relatives, in a class or in a group, today it requires recognition of “the specificity, beauty, and uniqueness” of each one. Moreover, if we are all brothers, then our way of conceiving reality changes, because we look at it from a specific perspective, which is that of the least ones, and we are pushed to act, as for example, to protect the fundamental rights of children, women, the elderly, the disabled and the oppressed”.

The protagonists are the ones who hope in a world of more justice, solidarity and peace. The Global Compact on Education, suggested by Pope Francis, speaks of youth as being, at the same time, both beneficiaries and agents in the field of education. Together with their “families, communities, schools, universities, institutions, religions and government” they are called “to subscribe to a global pact on education” and to commit themselves to a more fraternal and peaceful humanity. This was discussed during the meeting entitled “Together to look beyond”, held at the Pontifical Lateran University, in Rome on October 15. In a video message, the Holy Father urged all people of good will to adhere to the Pact. Silvia Cataldi, sociologist and professor at La Sapienza University in Rome commented on the Pope’s words In recent years we have noticed the youth’s sturdy protagonism where important current affairs are concerned. The educational model that sees them as passive subjects seems to be obsolete… “Often, educational models limit themselves to think of culture as a concept. The pedagogist Paulo Freire speaks of the “banking model of education”, where knowledge can be poured or deposited as if in a container. However, this knowledge has two risks: that of remaining abstract and detached from life, and that of assuming a hierarchical vision of knowledge. With respect to this, the Pact strikes me as an educator, because it invites us to listen to the cry of the younger generations, to let ourselves be questioned by their questions. We must realize that education is a participatory path, and not a unidirectional one”. So, what does to educate mean? “The term culture stems from colere and it means to cultivate, a verb which indicates that one needs to dedicate time and space, by starting from questions and not from providing answers. But it also means to take care, to love. This is why I am so impressed by the Pact, because it strongly affirms that “education is above all a matter of love”. When we speak of love we think of the heart, of feelings. But love has an eminently practical dimension, it requires hands. So, we educators do our work only if we manage to understand that education is care. Daily care is revolutionary because it is an element of criticism and of transformation of the world. Hannah Arendt explains this well when she says that “Education decides whether we love the world enough because it leads to its transformation”. How can we make sure that the Pact does not remain just an appeal? The call to universal brotherhood – the core of the Pact – has important implications, but to have a transforming power it must promote a change of perspective that leads one to welcome diversity and heal inequalities. The French sociologist Alain Caillé says that “fraternity is plural”, and this means that if in the past brotherhood was only among peers, relatives, in a class or in a group, today it requires recognition of “the specificity, beauty, and uniqueness” of each one. Moreover, if we are all brothers, then our way of conceiving reality changes, because we look at it from a specific perspective, which is that of the least ones, and we are pushed to act, as for example, to protect the fundamental rights of children, women, the elderly, the disabled and the oppressed”.

Claudia Di Lorenzi

Nov 11, 2020 | Non categorizzato

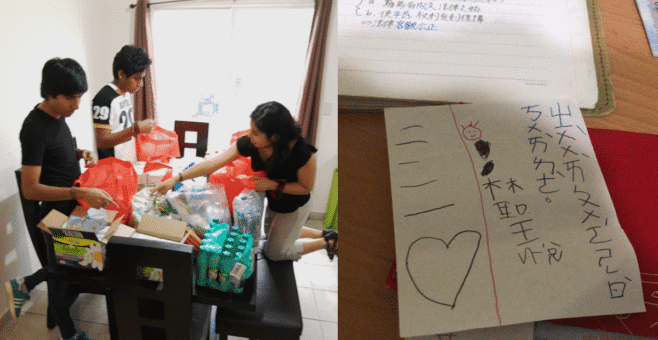

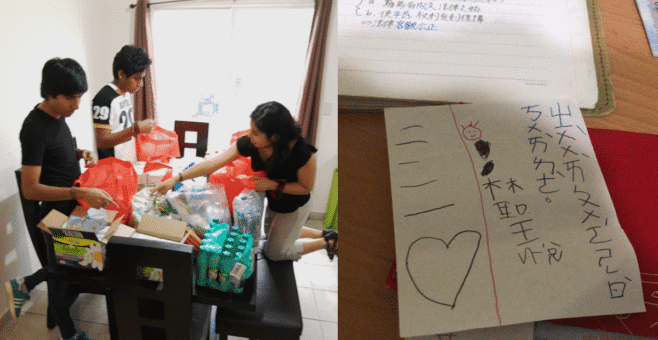

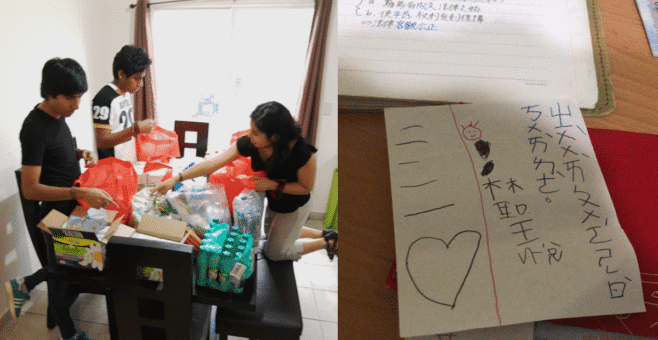

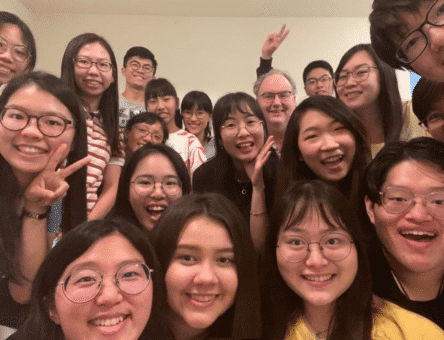

The commitment of the young people of the Ho Chi Minh City Focolare Movement in Vietnam for people in difficulty: to take care of their needs by distributing 300 parcels of goods to families and 370 small gifts for children.  In July 2020, some gen2 and youths of the Focolare in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam wanted to do something concrete for #daretocare – the focolare youth Campaign to “take responsibility” for our society and the planet -, to help people in the community who are in need. They chose to go and share their love to Cu M’gar district, Dak Lak province. It is a place with the widest coffee area and the people come from another ethnic group. It’s 8 hours’ drive from HCMC. “We started to pack and sell fruits, yogurt, and sweet potatoes online. We collected used clothes for adults and kids, we received some donations and at a certain point the restrictions for COVID19 was over so we were able to sell goods as “fundraising” at the parish. During the preparation, it was a big challenge for us to see things together, misunderstanding and disagreements were not lacking. But knowing that there will be 300 families who are waiting for us we continue to go ahead with love, patience and a little of sacrifice.

In July 2020, some gen2 and youths of the Focolare in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam wanted to do something concrete for #daretocare – the focolare youth Campaign to “take responsibility” for our society and the planet -, to help people in the community who are in need. They chose to go and share their love to Cu M’gar district, Dak Lak province. It is a place with the widest coffee area and the people come from another ethnic group. It’s 8 hours’ drive from HCMC. “We started to pack and sell fruits, yogurt, and sweet potatoes online. We collected used clothes for adults and kids, we received some donations and at a certain point the restrictions for COVID19 was over so we were able to sell goods as “fundraising” at the parish. During the preparation, it was a big challenge for us to see things together, misunderstanding and disagreements were not lacking. But knowing that there will be 300 families who are waiting for us we continue to go ahead with love, patience and a little of sacrifice.  On the 17 – 18 October with 30 energetic and enthusiastic youths, we made a meaningful trip. We were able to distribute 300 parcels of goods to the families and 370 small gifts for the kids. During the trip, we realized how lucky and happy we are compared to the situations of these families. We shared what we have brought to show our love but at the end we received more LOVE through their smiles… In fact, every time we approach them it seemed like we have known each other for a long time. During the trip some of the youths brought their friends. We found ourselves being together from different parts of Vietnam. There was a joy to know each one, to laugh and to work together like brothers and sisters without any distinctions. Thank you for this project #daretocare, a good excuse to work together and build this fraternal brotherhood among us”.

On the 17 – 18 October with 30 energetic and enthusiastic youths, we made a meaningful trip. We were able to distribute 300 parcels of goods to the families and 370 small gifts for the kids. During the trip, we realized how lucky and happy we are compared to the situations of these families. We shared what we have brought to show our love but at the end we received more LOVE through their smiles… In fact, every time we approach them it seemed like we have known each other for a long time. During the trip some of the youths brought their friends. We found ourselves being together from different parts of Vietnam. There was a joy to know each one, to laugh and to work together like brothers and sisters without any distinctions. Thank you for this project #daretocare, a good excuse to work together and build this fraternal brotherhood among us”.

Gen and youth of the Focolare Movement in Vietnam

Nov 9, 2020 | Non categorizzato

A communitarian spirituality also involves a communitarian “purification”, as Chiara Lubich explains in the following text. Just as loving our neighbour according to the Gospel brings great joy, so too a lack of relationships and of unity with others can cause suffering and pain. Since communitarian life must be fully personal as well, it is our general experience when we are alone that, after loving our brothers and sisters, we become aware of our union with God. … So it can be said that when we go to our brothers and sisters … by loving as the gospel teaches, we become more Christ, more truly human. And, since we try to be united with our brothers and sisters, in addition to silence we have a special love for the word, as a means of communication. We speak in order to become one with others. We speak, in the Movement, in order to share our experiences of living the Word of Life, or of our own spiritual life, aware that the fire that does not grow is extinguished and that this communion of soul has great spiritual value. Saint Lawrence Giustiniani said: “Nothing in the world gives more praise to God and reveals him as worthy of praise than the humble and fraternal exchange of spiritual gifts….”[1] When we do not speak, we write: we write letters, articles, books, diaries to advance the kingdom of God in our hearts. We use all the modern means of communication. … In the Movement we also practice those mortifications that are indispensable for every Christian life. We do penance, especially as recommended by the Church, but we have special regard for those penances that a life of unity with others entails. That is not easy, for the “old self,” as Paul[2], calls it, is always ready to find its way back into us. Fraternal unity is not established once for all; it must be renewed continually. When there is unity and through it Jesus is in our midst, we experience great joy, as promised by Jesus in his prayer for unity. When unity is compromised, the shadows and confusion return and we live in a kind of purgatory. That is the kind of penance we must be ready to practice. Here is where our love for Jesus crucified and forsaken, the key to unity, comes in. We must first resolve all our differences out of love for him, and make every effort to restore unity.

Chiara Lubich

Taken from: “A Spirituality of Communion” in Chiara Lubich: Essential Writings, New City Press, Hyde Park, New York 2007, pp. 30-31. [1] S. Lorenzo Giustiniani, Discipline and perfection in monastic life, Roma 1967, p.4. [2] The old self: in the Pauline meaning of a person imprisoned by their selfishness, cf. Eph: 4:22.

Nov 7, 2020 | Non categorizzato

Economist Luigino Bruni, one of the experts Pope Francis called to be part of the Vatican Covid-19 Commission is convinced that the lesson of the pandemic will help us rediscover the profound truth connected with the expression “common good”.  Healthcare, education, security – these are the linchpins of any nation which should not be subject to making a profit. Economist Luigino Bruni, one of the experts Pope Francis called to be part of the Vatican Covid-19 Commission (the “Covid-19: Building a Healthier Future” has been created in collaboration with the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development), is convinced that the lesson of the pandemic will help us rediscover the profound truth connected with the expression “common good”. This is so because, as he believes, everything is fundamentally a common good: politics in its true sense, the economy which looks to humanity before seeking to make a profit. In this new global vision that can be born after the pandemic, the Church, he states, must make itself a “guarantor” of this collective patrimony, in so far as it is lies outside the logic of commerce. Bruni’s hope is that this experience, conditioned by a virus that has no boundaries, will help us not forget “the importance of human cooperation and global solidarity”. You are part of the Vatican COVID 19 Commission, Pope Francis’ response mechanism to an unprecedented virus. What do you personally hope to learn from this experience? In what way do you think society as a whole can be inspired by the work of the Commission? The most important thing I have learned from this experience is the importance of the principle of precaution for the common good. Absent for the most part in the initial phase of the epidemic, the principle of precaution, one of the pillars of the Church’s social doctrine, tells us something extremely important. The principle of precaution is lived obsessively on the individual level (it’s enough to think of the insurance companies which seem to be taking over the world), but is completely absent on the collective level, and thus makes 21st century society extremely vulnerable. This is why those countries which have preserved a bit of a welfare state have demonstrated themselves a lot stronger than those governed entirely by the market And then the common good: since a common evil has revealed to us what the common good is, so has the pandemic forced us to see that the common good requires community, and not only the market. Health, safety, and education cannot be left to the game of profit. Pope Francis asked the COVID 19 Commission to prepare the future instead of prepare for it. What should be the role of the Catholic Church as an institution in this endeavor? The Catholic Church is one of the few (if not the only) institution that guarantees and safeguards the global common good. Having no private interests, it can pursue the good of all. It is because of this that she has a vast hearing. For the same reason, she has a responsibility to exercise it on a global scale. What personal lessons (if any) have you derived from the experience of the pandemic? What concrete changes do you hope to see after this crisis both personally and globally? The first lesson is the value of relational goods. Not being able to exchange hugs in these months, I have rediscovered the value of an embrace and of contact. Secondly, we can and must have many online meetings and working remotely, but for important decisions and for decisive meetings, the internet does not suffice. Physical presence is necessary. So, the virtual boom is making us discover the importance of flesh and blood contact and the intelligence of the human body. I hope that we do not forget the lessons learned in these months (because people forget very quickly), in particular the importance of politics as we have rediscovered in these months (as the art of the common good against a common evil), and that we do not forget the importance of human cooperation and global solidarity.

Healthcare, education, security – these are the linchpins of any nation which should not be subject to making a profit. Economist Luigino Bruni, one of the experts Pope Francis called to be part of the Vatican Covid-19 Commission (the “Covid-19: Building a Healthier Future” has been created in collaboration with the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development), is convinced that the lesson of the pandemic will help us rediscover the profound truth connected with the expression “common good”. This is so because, as he believes, everything is fundamentally a common good: politics in its true sense, the economy which looks to humanity before seeking to make a profit. In this new global vision that can be born after the pandemic, the Church, he states, must make itself a “guarantor” of this collective patrimony, in so far as it is lies outside the logic of commerce. Bruni’s hope is that this experience, conditioned by a virus that has no boundaries, will help us not forget “the importance of human cooperation and global solidarity”. You are part of the Vatican COVID 19 Commission, Pope Francis’ response mechanism to an unprecedented virus. What do you personally hope to learn from this experience? In what way do you think society as a whole can be inspired by the work of the Commission? The most important thing I have learned from this experience is the importance of the principle of precaution for the common good. Absent for the most part in the initial phase of the epidemic, the principle of precaution, one of the pillars of the Church’s social doctrine, tells us something extremely important. The principle of precaution is lived obsessively on the individual level (it’s enough to think of the insurance companies which seem to be taking over the world), but is completely absent on the collective level, and thus makes 21st century society extremely vulnerable. This is why those countries which have preserved a bit of a welfare state have demonstrated themselves a lot stronger than those governed entirely by the market And then the common good: since a common evil has revealed to us what the common good is, so has the pandemic forced us to see that the common good requires community, and not only the market. Health, safety, and education cannot be left to the game of profit. Pope Francis asked the COVID 19 Commission to prepare the future instead of prepare for it. What should be the role of the Catholic Church as an institution in this endeavor? The Catholic Church is one of the few (if not the only) institution that guarantees and safeguards the global common good. Having no private interests, it can pursue the good of all. It is because of this that she has a vast hearing. For the same reason, she has a responsibility to exercise it on a global scale. What personal lessons (if any) have you derived from the experience of the pandemic? What concrete changes do you hope to see after this crisis both personally and globally? The first lesson is the value of relational goods. Not being able to exchange hugs in these months, I have rediscovered the value of an embrace and of contact. Secondly, we can and must have many online meetings and working remotely, but for important decisions and for decisive meetings, the internet does not suffice. Physical presence is necessary. So, the virtual boom is making us discover the importance of flesh and blood contact and the intelligence of the human body. I hope that we do not forget the lessons learned in these months (because people forget very quickly), in particular the importance of politics as we have rediscovered in these months (as the art of the common good against a common evil), and that we do not forget the importance of human cooperation and global solidarity.  Preparing for the post-Covid world includes forming future generations, who will be forced to make decisions that forge new paths. In this sense, can education be considered only as a “cost” to reduce, even in times of crisis? Education, above all that of children and young people, is much more than an “expense”… It is a collective investment with the highest rate of social return. I hope that in those countries where schools are still closed, a national holiday will be designated when they are reopened. Democracy begins at the school desk and there it is born again in each generation. The first heritage (patres munus) that we pass on through the generations is that of education. Tens of millions of children around the world do not have access to education. Can article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights be ignored, which affirms that everyone has the right to free and mandatory education, at least regarding elementary education? Clearly this must not be ignored, but we cannot ask that the cost of education be entirely sustained by countries without sufficient resources. We must quickly give life to a new international cooperation under the slogan: “educating children and adolescents is a global common good”, where countries with more resources help those will fewer resources so that the right to free education becomes real. This pandemic has shown us that the world is a large community. We must transform this common evil into new common, global goods. Educational budgets have undergone sometimes drastic cuts even in rich countries. Could there really be a desire not to invest in future generations? If economic logic takes over, reasoning such as this will increase: “Why should I do something for future generations? What have they done for me?” If do ut des ‘(I’ll give something only if I get something out of it), the commercial mantra, becomes the new logic of nations, we will always invest less in education, and we will always create more debt which today’s children will pay off. We must become generous once again and cultivate non-economic virtues such as compassion, meekness, and generosity. Though it finds itself in economic difficulty, the Catholic Church is on the front lines offering education to the poorest. As we’ve seen during this pandemic, lockdowns have had a considerable impact on Catholic schools. But the Church continues to welcome everyone, without distinctions based on creed, making space for encounter and dialogue. How important is this aspect? The Church has always been an institution for the common good. Luke’s parable does not tells us about the faith of the half-dead man who the Good Samaritan assisted. It is precisely during the gravest crises that the Church rediscovers her vocation as Mater et magister (Mother and teacher), that the esteem of non-Christians grows toward her, that the sea that gathers everything in, then gives everything to everyone, above all to the poorest. The Church has always known, after all, that the indicator of every common good is the condition of the poorest. What contribution can education about religion and religions offer young people, especially in a world increasingly driven by divisions and which fosters the engagement of fear and tension? That depends on how they are taught. The ethical dimension which exists in every religion is not enough. The main teaching that religions can offer today regards the interior life and spirituality, because our generation, in the space of just a few decades, has squandered a thousand-year-old heritage which contained ancient wisdom and popular piety. The world’s religions must help the young and everyone else to rewrite a new “grammar” of the interior life. If they do not do that, depression will become the plague of the 21st century.

Preparing for the post-Covid world includes forming future generations, who will be forced to make decisions that forge new paths. In this sense, can education be considered only as a “cost” to reduce, even in times of crisis? Education, above all that of children and young people, is much more than an “expense”… It is a collective investment with the highest rate of social return. I hope that in those countries where schools are still closed, a national holiday will be designated when they are reopened. Democracy begins at the school desk and there it is born again in each generation. The first heritage (patres munus) that we pass on through the generations is that of education. Tens of millions of children around the world do not have access to education. Can article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights be ignored, which affirms that everyone has the right to free and mandatory education, at least regarding elementary education? Clearly this must not be ignored, but we cannot ask that the cost of education be entirely sustained by countries without sufficient resources. We must quickly give life to a new international cooperation under the slogan: “educating children and adolescents is a global common good”, where countries with more resources help those will fewer resources so that the right to free education becomes real. This pandemic has shown us that the world is a large community. We must transform this common evil into new common, global goods. Educational budgets have undergone sometimes drastic cuts even in rich countries. Could there really be a desire not to invest in future generations? If economic logic takes over, reasoning such as this will increase: “Why should I do something for future generations? What have they done for me?” If do ut des ‘(I’ll give something only if I get something out of it), the commercial mantra, becomes the new logic of nations, we will always invest less in education, and we will always create more debt which today’s children will pay off. We must become generous once again and cultivate non-economic virtues such as compassion, meekness, and generosity. Though it finds itself in economic difficulty, the Catholic Church is on the front lines offering education to the poorest. As we’ve seen during this pandemic, lockdowns have had a considerable impact on Catholic schools. But the Church continues to welcome everyone, without distinctions based on creed, making space for encounter and dialogue. How important is this aspect? The Church has always been an institution for the common good. Luke’s parable does not tells us about the faith of the half-dead man who the Good Samaritan assisted. It is precisely during the gravest crises that the Church rediscovers her vocation as Mater et magister (Mother and teacher), that the esteem of non-Christians grows toward her, that the sea that gathers everything in, then gives everything to everyone, above all to the poorest. The Church has always known, after all, that the indicator of every common good is the condition of the poorest. What contribution can education about religion and religions offer young people, especially in a world increasingly driven by divisions and which fosters the engagement of fear and tension? That depends on how they are taught. The ethical dimension which exists in every religion is not enough. The main teaching that religions can offer today regards the interior life and spirituality, because our generation, in the space of just a few decades, has squandered a thousand-year-old heritage which contained ancient wisdom and popular piety. The world’s religions must help the young and everyone else to rewrite a new “grammar” of the interior life. If they do not do that, depression will become the plague of the 21st century.

Source: Vatican News

Click here to see the interview

Nov 5, 2020 | Non categorizzato

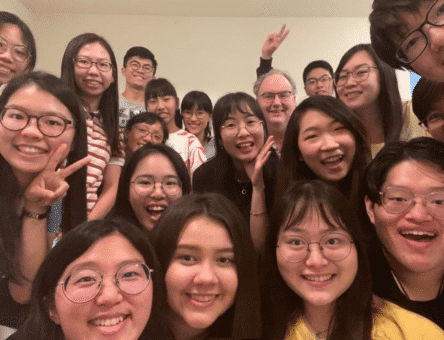

In recent months the communion of goods has developed even more among the Focolare communities around the world, responding to many requests for help. The extraordinary communion of goods for the Covid-19 emergency is once again helping us to experience the reality of “always being family” which knows no boundaries or differences but builds universal brotherhood as endorsed by Pope Francis in his latest encyclical “Fratelli tutti”. This communion is developed through very real “fioretti” (“little flowers”) or acts of love and reminds us of the experience of the first Christians: knowing they were of one heart and one soul, they put all their goods in common, bearing witness to God’s superabundant love and bringing hope. During these months of pandemic, the communion of goods has grown even stronger between various communities of the Focolare Movement around the world, in response to many requests for help.  In Asia, Taiwan and Japan, the Gen who are the young people of the Focolare started a fundraiser to help the community in the city of Torreón, Mexico. Ròisìn, a Gen from Taiwan immediately felt the urge to act when she heard how the Mexican Gen were helping poor families affected by the virus. Together with other Gen in her city she launched an appeal to the entire Focolare community in Taiwan who immediately joined the initiative by raising funds for their friends in Mexico. Subsequently, the Gen of Japan also joined the initiative. In Tanzania, one of the families in the community was without light because the battery of the small solar system had stopped working. “Some time before,” the local community wrote, “one of us had received a grant of 50 Euros, about 120,000 Tanzanian shellini, for a family in difficulty. We talked about it together and decided to give the money which covered about 60% of the cost. The family was able to buy a new battery with the money and get light back into the house. After a few days, a donation of 1,000,000,000 Tanzanian shellini arrived for the needs of the focolare: almost 10 times as much…the hundredfold!!!”.

In Asia, Taiwan and Japan, the Gen who are the young people of the Focolare started a fundraiser to help the community in the city of Torreón, Mexico. Ròisìn, a Gen from Taiwan immediately felt the urge to act when she heard how the Mexican Gen were helping poor families affected by the virus. Together with other Gen in her city she launched an appeal to the entire Focolare community in Taiwan who immediately joined the initiative by raising funds for their friends in Mexico. Subsequently, the Gen of Japan also joined the initiative. In Tanzania, one of the families in the community was without light because the battery of the small solar system had stopped working. “Some time before,” the local community wrote, “one of us had received a grant of 50 Euros, about 120,000 Tanzanian shellini, for a family in difficulty. We talked about it together and decided to give the money which covered about 60% of the cost. The family was able to buy a new battery with the money and get light back into the house. After a few days, a donation of 1,000,000,000 Tanzanian shellini arrived for the needs of the focolare: almost 10 times as much…the hundredfold!!!”.  In Portugal, after hearing about the global situation from the International Focolare Centre, the local community decided to broaden its horizons beyond its borders. “The money we have collected so far – they write to us – is the result of small sacrifices as well as larger sums of money that we had not expected to receive. We see that there is a growing awareness of communion in everyone’s daily life: together we can try to not only overcome the difficulties caused by the pandemic but also create a way of life”. In Ecuador, J.V. managed to involve lots of people in the culture of giving. It all started with “a phone call to a colleague to hear how he was,” he says, “and to share his concerns about his family and the people in his village who had no food. He opened a Facebook page and started sending e-mails to publicize the precarious situation in this village. This prompted an incredibly generous response not only from the inhabitants of his neighbourhood but also from further afield. The colleague’s friends and family can now buy food and even help others whose needs are even greater than theirs. In Egypt everything is closed because of the lockdown, including the work of the “United World” foundation which transmits the culture of “universal brotherhood” through development projects supporting people living in fragile social situations. They asked themselves what they could do and where they could help. And so, in spite of the lockdown and “through the communities of various churches, mosques and other social organizations, we have been able to help an even larger number of people: families from the poorest districts of Cairo, widows, orphans, people on their own and elderly people, refugees from Ethiopia, Eritrea, North and South Sudan. At the moment we are able to prepare 700 packages of essential foodstuffs. Our goal is to reach 1,000 packages”. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Gen of Kinshasa started a communion of goods which consisted of setting up a fund to help those most in need. Nine families have received soap, sugar, rice and face masks. These experiences are about more than just providing financial help. As Ròisìn from Taiwan said, “even the darkest times can be enlightened by love and solidarity, and even if we are isolated from one another, we are closer to achieving a united world”.

In Portugal, after hearing about the global situation from the International Focolare Centre, the local community decided to broaden its horizons beyond its borders. “The money we have collected so far – they write to us – is the result of small sacrifices as well as larger sums of money that we had not expected to receive. We see that there is a growing awareness of communion in everyone’s daily life: together we can try to not only overcome the difficulties caused by the pandemic but also create a way of life”. In Ecuador, J.V. managed to involve lots of people in the culture of giving. It all started with “a phone call to a colleague to hear how he was,” he says, “and to share his concerns about his family and the people in his village who had no food. He opened a Facebook page and started sending e-mails to publicize the precarious situation in this village. This prompted an incredibly generous response not only from the inhabitants of his neighbourhood but also from further afield. The colleague’s friends and family can now buy food and even help others whose needs are even greater than theirs. In Egypt everything is closed because of the lockdown, including the work of the “United World” foundation which transmits the culture of “universal brotherhood” through development projects supporting people living in fragile social situations. They asked themselves what they could do and where they could help. And so, in spite of the lockdown and “through the communities of various churches, mosques and other social organizations, we have been able to help an even larger number of people: families from the poorest districts of Cairo, widows, orphans, people on their own and elderly people, refugees from Ethiopia, Eritrea, North and South Sudan. At the moment we are able to prepare 700 packages of essential foodstuffs. Our goal is to reach 1,000 packages”. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Gen of Kinshasa started a communion of goods which consisted of setting up a fund to help those most in need. Nine families have received soap, sugar, rice and face masks. These experiences are about more than just providing financial help. As Ròisìn from Taiwan said, “even the darkest times can be enlightened by love and solidarity, and even if we are isolated from one another, we are closer to achieving a united world”.

Lorenzo Russo

If you want to make your contribution to help those suffering from the effects of the global Covid crisis, go to this link

The virtual seminar entitled Latin America: Church, Pope Francis and the pandemic scenario will take place on November 19th and 20th 2020 and will be open to all those interested in this part of the world, which is also heavily affected by the virus; a situation already problematic due to many areas of poverty and marginalisation. The event aims to reflect on and analyse the pandemic situation on the Latin American continent, its consequences and, above all, the proposals of action and of aid from governments and from the Church. It is organised by the Pontifical Commission for Latin America, the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences and by the Latin American Episcopal Conference (CELAM), The Pope will contribute with a video-message. Contributions will also be made by Card. Marc Ouellet, President of the Pontifical Commission for Latin America, Mgr Miguel Cabrejos Vidarte, President of CELAM, Carlos Afonso Nobre, Nobel Peace Prize winner in 2007, the economist Jeffrey D. Sachs, Director of the entre for Sustainable Development at Columbia University and Gustavo Beliz, Secretary for Strategic Affairs of the Argentinean Presidency. The introductory note to the seminar explains that to date, on the Latin American continent, as in the rest of the world, it is impossible to calculate the damage of the pandemic: “In many cases, the negative effects of border closures and the consequent social and economic repercussions were only the beginning of a spiral of damage not yet quantified, and even less a medium-term solution”. For this reason, the seminar will be an opportunity for the missionary and pastoral work of the Catholic Church and the contribution of various specialists from the world of economics and politics to meet and dialogue in order to strengthen a cultural and operational network and thus ensure a better future for the continent. Pope Francis will also participate at the presentation of the Task Force against Covid-19, established by him and represented at the seminar by its head who will present the work of the Task Force. In times of uncertainty and lack of future, the Church looks to the “continent of hope” and seeks shared instruments that can transform the crisis into opportunities or at least find a way out. For the programme of the event sign in here

The virtual seminar entitled Latin America: Church, Pope Francis and the pandemic scenario will take place on November 19th and 20th 2020 and will be open to all those interested in this part of the world, which is also heavily affected by the virus; a situation already problematic due to many areas of poverty and marginalisation. The event aims to reflect on and analyse the pandemic situation on the Latin American continent, its consequences and, above all, the proposals of action and of aid from governments and from the Church. It is organised by the Pontifical Commission for Latin America, the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences and by the Latin American Episcopal Conference (CELAM), The Pope will contribute with a video-message. Contributions will also be made by Card. Marc Ouellet, President of the Pontifical Commission for Latin America, Mgr Miguel Cabrejos Vidarte, President of CELAM, Carlos Afonso Nobre, Nobel Peace Prize winner in 2007, the economist Jeffrey D. Sachs, Director of the entre for Sustainable Development at Columbia University and Gustavo Beliz, Secretary for Strategic Affairs of the Argentinean Presidency. The introductory note to the seminar explains that to date, on the Latin American continent, as in the rest of the world, it is impossible to calculate the damage of the pandemic: “In many cases, the negative effects of border closures and the consequent social and economic repercussions were only the beginning of a spiral of damage not yet quantified, and even less a medium-term solution”. For this reason, the seminar will be an opportunity for the missionary and pastoral work of the Catholic Church and the contribution of various specialists from the world of economics and politics to meet and dialogue in order to strengthen a cultural and operational network and thus ensure a better future for the continent. Pope Francis will also participate at the presentation of the Task Force against Covid-19, established by him and represented at the seminar by its head who will present the work of the Task Force. In times of uncertainty and lack of future, the Church looks to the “continent of hope” and seeks shared instruments that can transform the crisis into opportunities or at least find a way out. For the programme of the event sign in here

In July 2020, some gen2 and youths of the Focolare in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam wanted to do something concrete for #daretocare – the focolare youth Campaign to “take responsibility” for our society and the planet -, to help people in the community who are in need. They chose to go and share their love to Cu M’gar district, Dak Lak province. It is a place with the widest coffee area and the people come from another ethnic group. It’s 8 hours’ drive from HCMC. “We started to pack and sell fruits, yogurt, and sweet potatoes online. We collected used clothes for adults and kids, we received some donations and at a certain point the restrictions for COVID19 was over so we were able to sell goods as “fundraising” at the parish. During the preparation, it was a big challenge for us to see things together, misunderstanding and disagreements were not lacking. But knowing that there will be 300 families who are waiting for us we continue to go ahead with love, patience and a little of sacrifice.

In July 2020, some gen2 and youths of the Focolare in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam wanted to do something concrete for #daretocare – the focolare youth Campaign to “take responsibility” for our society and the planet -, to help people in the community who are in need. They chose to go and share their love to Cu M’gar district, Dak Lak province. It is a place with the widest coffee area and the people come from another ethnic group. It’s 8 hours’ drive from HCMC. “We started to pack and sell fruits, yogurt, and sweet potatoes online. We collected used clothes for adults and kids, we received some donations and at a certain point the restrictions for COVID19 was over so we were able to sell goods as “fundraising” at the parish. During the preparation, it was a big challenge for us to see things together, misunderstanding and disagreements were not lacking. But knowing that there will be 300 families who are waiting for us we continue to go ahead with love, patience and a little of sacrifice.

Healthcare, education, security – these are the linchpins of any nation which should not be subject to making a profit. Economist Luigino Bruni, one of the experts Pope Francis called to be part of the Vatican Covid-19 Commission (the “Covid-19: Building a Healthier Future” has been created in collaboration with the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development), is convinced that the lesson of the pandemic will help us rediscover the profound truth connected with the expression “common good”. This is so because, as he believes, everything is fundamentally a common good: politics in its true sense, the economy which looks to humanity before seeking to make a profit. In this new global vision that can be born after the pandemic, the Church, he states, must make itself a “guarantor” of this collective patrimony, in so far as it is lies outside the logic of commerce. Bruni’s hope is that this experience, conditioned by a virus that has no boundaries, will help us not forget “the importance of human cooperation and global solidarity”. You are part of the Vatican COVID 19 Commission, Pope Francis’ response mechanism to an unprecedented virus. What do you personally hope to learn from this experience? In what way do you think society as a whole can be inspired by the work of the Commission? The most important thing I have learned from this experience is the importance of the principle of precaution for the common good. Absent for the most part in the initial phase of the epidemic, the principle of precaution, one of the pillars of the Church’s social doctrine, tells us something extremely important. The principle of precaution is lived obsessively on the individual level (it’s enough to think of the insurance companies which seem to be taking over the world), but is completely absent on the collective level, and thus makes 21st century society extremely vulnerable. This is why those countries which have preserved a bit of a welfare state have demonstrated themselves a lot stronger than those governed entirely by the market And then the common good: since a common evil has revealed to us what the common good is, so has the pandemic forced us to see that the common good requires community, and not only the market. Health, safety, and education cannot be left to the game of profit. Pope Francis asked the COVID 19 Commission to prepare the future instead of prepare for it. What should be the role of the Catholic Church as an institution in this endeavor? The Catholic Church is one of the few (if not the only) institution that guarantees and safeguards the global common good. Having no private interests, it can pursue the good of all. It is because of this that she has a vast hearing. For the same reason, she has a responsibility to exercise it on a global scale. What personal lessons (if any) have you derived from the experience of the pandemic? What concrete changes do you hope to see after this crisis both personally and globally? The first lesson is the value of relational goods. Not being able to exchange hugs in these months, I have rediscovered the value of an embrace and of contact. Secondly, we can and must have many online meetings and working remotely, but for important decisions and for decisive meetings, the internet does not suffice. Physical presence is necessary. So, the virtual boom is making us discover the importance of flesh and blood contact and the intelligence of the human body. I hope that we do not forget the lessons learned in these months (because people forget very quickly), in particular the importance of politics as we have rediscovered in these months (as the art of the common good against a common evil), and that we do not forget the importance of human cooperation and global solidarity.

Healthcare, education, security – these are the linchpins of any nation which should not be subject to making a profit. Economist Luigino Bruni, one of the experts Pope Francis called to be part of the Vatican Covid-19 Commission (the “Covid-19: Building a Healthier Future” has been created in collaboration with the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development), is convinced that the lesson of the pandemic will help us rediscover the profound truth connected with the expression “common good”. This is so because, as he believes, everything is fundamentally a common good: politics in its true sense, the economy which looks to humanity before seeking to make a profit. In this new global vision that can be born after the pandemic, the Church, he states, must make itself a “guarantor” of this collective patrimony, in so far as it is lies outside the logic of commerce. Bruni’s hope is that this experience, conditioned by a virus that has no boundaries, will help us not forget “the importance of human cooperation and global solidarity”. You are part of the Vatican COVID 19 Commission, Pope Francis’ response mechanism to an unprecedented virus. What do you personally hope to learn from this experience? In what way do you think society as a whole can be inspired by the work of the Commission? The most important thing I have learned from this experience is the importance of the principle of precaution for the common good. Absent for the most part in the initial phase of the epidemic, the principle of precaution, one of the pillars of the Church’s social doctrine, tells us something extremely important. The principle of precaution is lived obsessively on the individual level (it’s enough to think of the insurance companies which seem to be taking over the world), but is completely absent on the collective level, and thus makes 21st century society extremely vulnerable. This is why those countries which have preserved a bit of a welfare state have demonstrated themselves a lot stronger than those governed entirely by the market And then the common good: since a common evil has revealed to us what the common good is, so has the pandemic forced us to see that the common good requires community, and not only the market. Health, safety, and education cannot be left to the game of profit. Pope Francis asked the COVID 19 Commission to prepare the future instead of prepare for it. What should be the role of the Catholic Church as an institution in this endeavor? The Catholic Church is one of the few (if not the only) institution that guarantees and safeguards the global common good. Having no private interests, it can pursue the good of all. It is because of this that she has a vast hearing. For the same reason, she has a responsibility to exercise it on a global scale. What personal lessons (if any) have you derived from the experience of the pandemic? What concrete changes do you hope to see after this crisis both personally and globally? The first lesson is the value of relational goods. Not being able to exchange hugs in these months, I have rediscovered the value of an embrace and of contact. Secondly, we can and must have many online meetings and working remotely, but for important decisions and for decisive meetings, the internet does not suffice. Physical presence is necessary. So, the virtual boom is making us discover the importance of flesh and blood contact and the intelligence of the human body. I hope that we do not forget the lessons learned in these months (because people forget very quickly), in particular the importance of politics as we have rediscovered in these months (as the art of the common good against a common evil), and that we do not forget the importance of human cooperation and global solidarity.

In Asia, Taiwan and Japan, the Gen who are the young people of the Focolare started a fundraiser to help the community in the city of Torreón, Mexico. Ròisìn, a Gen from Taiwan immediately felt the urge to act when she heard how the Mexican Gen were helping poor families affected by the virus. Together with other Gen in her city she launched an appeal to the entire Focolare community in Taiwan who immediately joined the initiative by raising funds for their friends in Mexico. Subsequently, the Gen of Japan also joined the initiative. In Tanzania, one of the families in the community was without light because the battery of the small solar system had stopped working. “Some time before,” the local community wrote, “one of us had received a grant of 50 Euros, about 120,000 Tanzanian shellini, for a family in difficulty. We talked about it together and decided to give the money which covered about 60% of the cost. The family was able to buy a new battery with the money and get light back into the house. After a few days, a donation of 1,000,000,000 Tanzanian shellini arrived for the needs of the focolare: almost 10 times as much…the hundredfold!!!”.

In Asia, Taiwan and Japan, the Gen who are the young people of the Focolare started a fundraiser to help the community in the city of Torreón, Mexico. Ròisìn, a Gen from Taiwan immediately felt the urge to act when she heard how the Mexican Gen were helping poor families affected by the virus. Together with other Gen in her city she launched an appeal to the entire Focolare community in Taiwan who immediately joined the initiative by raising funds for their friends in Mexico. Subsequently, the Gen of Japan also joined the initiative. In Tanzania, one of the families in the community was without light because the battery of the small solar system had stopped working. “Some time before,” the local community wrote, “one of us had received a grant of 50 Euros, about 120,000 Tanzanian shellini, for a family in difficulty. We talked about it together and decided to give the money which covered about 60% of the cost. The family was able to buy a new battery with the money and get light back into the house. After a few days, a donation of 1,000,000,000 Tanzanian shellini arrived for the needs of the focolare: almost 10 times as much…the hundredfold!!!”.