The Focolare thanks everyone

Members of the Focolare community in Milan welcomes Maria Voce.

Members of the Focolare community in Milan welcomes Maria Voce.

We can experience a new peace and a surprising joy when we forgive properly, realistically, sincerely. It is our ‘vendetta of love’. In a violent society such as the one we live in, forgiveness is a difficult issue to face. How can you forgive someone who has destroyed your family, committed unspeakable acts of criminality or, more simply, has deeply hurt you in personal matters, ruining your career or betraying your trust? The first instinctive reaction is to get your own back, rendering evil for evil, unleashing a spiral of hatred and aggression, and increasing barbarism in society. Or else it causes a breakdown in relations, nursing grudges and spite, an attitude that embitters life and poisons relationships. The Word of God erupts with force in the most varied situations of conflict and proposes, uncompromisingly, the most difficult and bravest solution: forgiveness. The invitation this time comes from a wise man from the ancient people of Israel, Ben Sirach, who shows how absurd it is to ask forgiveness of God if, in turn, you do not know how to forgive. And in an ancient text from Jewish tradition we read: ‘To whom does God pardon iniquity? To whoever pardons the wrongs done by others.’1 It is what Jesus himself taught in our prayer to the Father: ‘Father … forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.’2 We too make mistakes, and every time we wish to be forgiven! We beg humbly and hope that we will be given again the chance for a new start, that we will be trusted once more. If it is like that for us, will it not be so also for others? Must we not love our neighbour as ourselves? Chiara Lubich, who continues to inspire our understanding of the Word, commented on the invitation to forgive in this way: ‘It is not the kind of forgetfulness that means not looking reality in the face. Forgiveness is not weakness, which is to say it is not failing out of fear of the strong to take account of the wrong they have done. Forgiveness is not about saying that something serious does not matter, or calling good what is evil. Forgiveness is not indifference. Forgiveness is an act of will and of clear thinking, and so of freedom. It is about accepting our brother or sister as they are, despite the wrong that has been committed, as God accepts us sinners, despite our defects. Forgiveness is about not responding to an affront with an affront, but it does as Paul says: “Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good” (Rom 12:21). ‘Forgiveness is about opening up for whoever does you wrong the possibility of a new relationship with you. So it gives the possibility for the two of you to begin life again, to have a future where evil does not have the last word.’ The Word of Life will help us resist the temptation of replying in kind, of immediately getting our own back. It will help us to see whoever is our ‘enemy’ with new eyes, recognizing them as a brother or sister. However bad they may be, they need someone to love them, to help them to change. It will be our ‘vendetta of love’. Chiara went on to explain: ‘You will say, “But it’s impossible.” That’s understandable. But here is the beauty of Christianity. It is not for nothing that you follow a God who, dying upon the cross, asked his Father to forgive those who killed him. Take courage. New life starts here. I can assure you, you will have a peace never tasted till now and a huge but surprising new joy.’3

Fr Fabio Ciardi, OMI

1 See Babylonian Talmud, Megillah 28a

2 See Mt 6:12 3 Costruire sulla roccia, Rome: Città Nuova, 1983, pp. 46-58

Subscribe to the monthly Word of Life (UK) October Word of Life (Living City Magazine – New York)

“I go back after 5 years. The impact is shocking. I don’t recognize Venezuela. The description given to me by the young man sitting next to me on the plane expresses the suffering of an afflicted but unresigned people. ‘I still have a bit of hope!’ he said to me as he described the beautiful sites in his country and invited to visit them. There’s a sense of emptiness in Caracas. Only the children provide a touch of liveliness to the absurd-looking reality. The journey to Puerto Ayucucho lasts 17 hours. Along the way my gaze is fixed on a girl rummaging in the garbage bins, looking for something to eat. But it is mostly the news of two boys 14 and 15 years old who were killed when caught stealing some mangos from a tree, that highlights the level of fear and non-sharing that has been reached. This is another form of homicide that is caused by hunger. The city is on the Colombia border. Its festering wound is represented in the murders of young people who, in the eyes of those who should protect them, appear to be violent thieves to be served the ulitmate punishment. This is also what happened to Felipe Andrés, a young seventeen-year-old who protected his brother by not telling those who had taken Felipe from his grandmother’s house where his brother could be found. Because of that he was brutally murdered with 17 bullets to match his age.

“I go back after 5 years. The impact is shocking. I don’t recognize Venezuela. The description given to me by the young man sitting next to me on the plane expresses the suffering of an afflicted but unresigned people. ‘I still have a bit of hope!’ he said to me as he described the beautiful sites in his country and invited to visit them. There’s a sense of emptiness in Caracas. Only the children provide a touch of liveliness to the absurd-looking reality. The journey to Puerto Ayucucho lasts 17 hours. Along the way my gaze is fixed on a girl rummaging in the garbage bins, looking for something to eat. But it is mostly the news of two boys 14 and 15 years old who were killed when caught stealing some mangos from a tree, that highlights the level of fear and non-sharing that has been reached. This is another form of homicide that is caused by hunger. The city is on the Colombia border. Its festering wound is represented in the murders of young people who, in the eyes of those who should protect them, appear to be violent thieves to be served the ulitmate punishment. This is also what happened to Felipe Andrés, a young seventeen-year-old who protected his brother by not telling those who had taken Felipe from his grandmother’s house where his brother could be found. Because of that he was brutally murdered with 17 bullets to match his age.  We’re in one of the quarters outside Valencia. I’m surprised by the queue for buying gas tanks. Twelve year-old Angel, candid as an angel, confides with disarming simplicity: ‘I don’t grow because I never drink milk.’ Even powdered milk is a luxury item in this country. I’m left impressed by the lively, simple gazes of the little ones I have met. An evening with the youth. You can feel their strong and palpable desire for redemption. Their experiences strengthen their desire to be carriers of hope, beginning with their friends at school, at work…. La Nuvoletta. A minibus takes us up to the Mariapolis Centre called La Nuvoletta. On the way we pass through some poverty-stricken areas. Here too, we find long queues of people hoping to be able to buy at least something. Gabriel thanks me for the lunch I offered him. ‘You know, I only eat pasta on Sunday.’ ‘And the other days?’ I ask. ‘On the other days, only sopa.’ I ask him if he likes being with people. “Yes,” he tells me, “because here everybody’s happy.”

We’re in one of the quarters outside Valencia. I’m surprised by the queue for buying gas tanks. Twelve year-old Angel, candid as an angel, confides with disarming simplicity: ‘I don’t grow because I never drink milk.’ Even powdered milk is a luxury item in this country. I’m left impressed by the lively, simple gazes of the little ones I have met. An evening with the youth. You can feel their strong and palpable desire for redemption. Their experiences strengthen their desire to be carriers of hope, beginning with their friends at school, at work…. La Nuvoletta. A minibus takes us up to the Mariapolis Centre called La Nuvoletta. On the way we pass through some poverty-stricken areas. Here too, we find long queues of people hoping to be able to buy at least something. Gabriel thanks me for the lunch I offered him. ‘You know, I only eat pasta on Sunday.’ ‘And the other days?’ I ask. ‘On the other days, only sopa.’ I ask him if he likes being with people. “Yes,” he tells me, “because here everybody’s happy.”  At the departure time, another bombshell: I learn that Fabián, such an innocent and lively child, had lost his father a few months earlier, murded by assassins. It felt like I was reliving my own experience: the illness and death of my father, which led me back to God. We look at each other and seem to understand one another. We arrive in Maracaibo, the hottest city in Venezuela. We look around and travel the 8 or more kilometres across the bridge that connects Maracaibo to San Francisco. A day with the Young For Unity awaits us in Tamale. Hearing a thirteen-year-old say: “I encouraged my mother to forgive those who had killed my father,” cannot leave you indifferent. The next appointment was in a parish. They greeted us with songs and then the dicusssion began: ‘What do you do when a kid tells you that he doesn’t go home because there’s nothing to eat?’ I try to respond by talking about the suffering and silence on the part of God that Jesus felt on the Cross. We say goodbye with a thought that one of the boys shared with everyone: ‘The strength of love is stronger than suffering’.” (A. S.)

At the departure time, another bombshell: I learn that Fabián, such an innocent and lively child, had lost his father a few months earlier, murded by assassins. It felt like I was reliving my own experience: the illness and death of my father, which led me back to God. We look at each other and seem to understand one another. We arrive in Maracaibo, the hottest city in Venezuela. We look around and travel the 8 or more kilometres across the bridge that connects Maracaibo to San Francisco. A day with the Young For Unity awaits us in Tamale. Hearing a thirteen-year-old say: “I encouraged my mother to forgive those who had killed my father,” cannot leave you indifferent. The next appointment was in a parish. They greeted us with songs and then the dicusssion began: ‘What do you do when a kid tells you that he doesn’t go home because there’s nothing to eat?’ I try to respond by talking about the suffering and silence on the part of God that Jesus felt on the Cross. We say goodbye with a thought that one of the boys shared with everyone: ‘The strength of love is stronger than suffering’.” (A. S.)

During the summer of 1949 Chiara Lubich, who was 29 years old at the time, had an experience of light and life. Leaving that “paradise” up in the mountains was very difficult, but she understood that God wanted her to be immersed in the sufferings of humanity “drying up the waters of tribulation” in those who suffer the most. There and then she wrote these words: “I have only one Spouse on earth: Jesus Forsaken. I have no other God but Him. In Him there is the whole of Paradise with the Trinity and the whole of the earth with Humanity. Therefore what is His is mine, and nothing else. And His is universal Pain, and therefore mine. I will go through the world seeking Him in every instant of my life. What hurts me is mine. Mine the pain that grazes me in the present. Mine the pain of the souls beside me (that is my Jesus). Mine all that is not peace, joy, beautiful, lovable, serene… in a word, what is not Paradise. Because I too have my Paradise, but is that in my Spouse’s heart. I know no other. So it will be for the years I have left: athirst for pain, for anguish, for despair, for sadness, for separation, for exile, for forsakenness, for torment, for… all that is Him, and He is Sin, Hell. In this way I will dry up the waters of tribulation in many hearts nearby and, through communion with my almighty Spouse, in many far away. I shall pass as a Fire that consumes all that must fall and leaves standing only the Truth. But it is necessary to be like Him: to be Him in the present moment of life.” From: Chiara Lubich, The Cry, Ed. New City London (pp. 61-2)

During the summer of 1949 Chiara Lubich, who was 29 years old at the time, had an experience of light and life. Leaving that “paradise” up in the mountains was very difficult, but she understood that God wanted her to be immersed in the sufferings of humanity “drying up the waters of tribulation” in those who suffer the most. There and then she wrote these words: “I have only one Spouse on earth: Jesus Forsaken. I have no other God but Him. In Him there is the whole of Paradise with the Trinity and the whole of the earth with Humanity. Therefore what is His is mine, and nothing else. And His is universal Pain, and therefore mine. I will go through the world seeking Him in every instant of my life. What hurts me is mine. Mine the pain that grazes me in the present. Mine the pain of the souls beside me (that is my Jesus). Mine all that is not peace, joy, beautiful, lovable, serene… in a word, what is not Paradise. Because I too have my Paradise, but is that in my Spouse’s heart. I know no other. So it will be for the years I have left: athirst for pain, for anguish, for despair, for sadness, for separation, for exile, for forsakenness, for torment, for… all that is Him, and He is Sin, Hell. In this way I will dry up the waters of tribulation in many hearts nearby and, through communion with my almighty Spouse, in many far away. I shall pass as a Fire that consumes all that must fall and leaves standing only the Truth. But it is necessary to be like Him: to be Him in the present moment of life.” From: Chiara Lubich, The Cry, Ed. New City London (pp. 61-2)

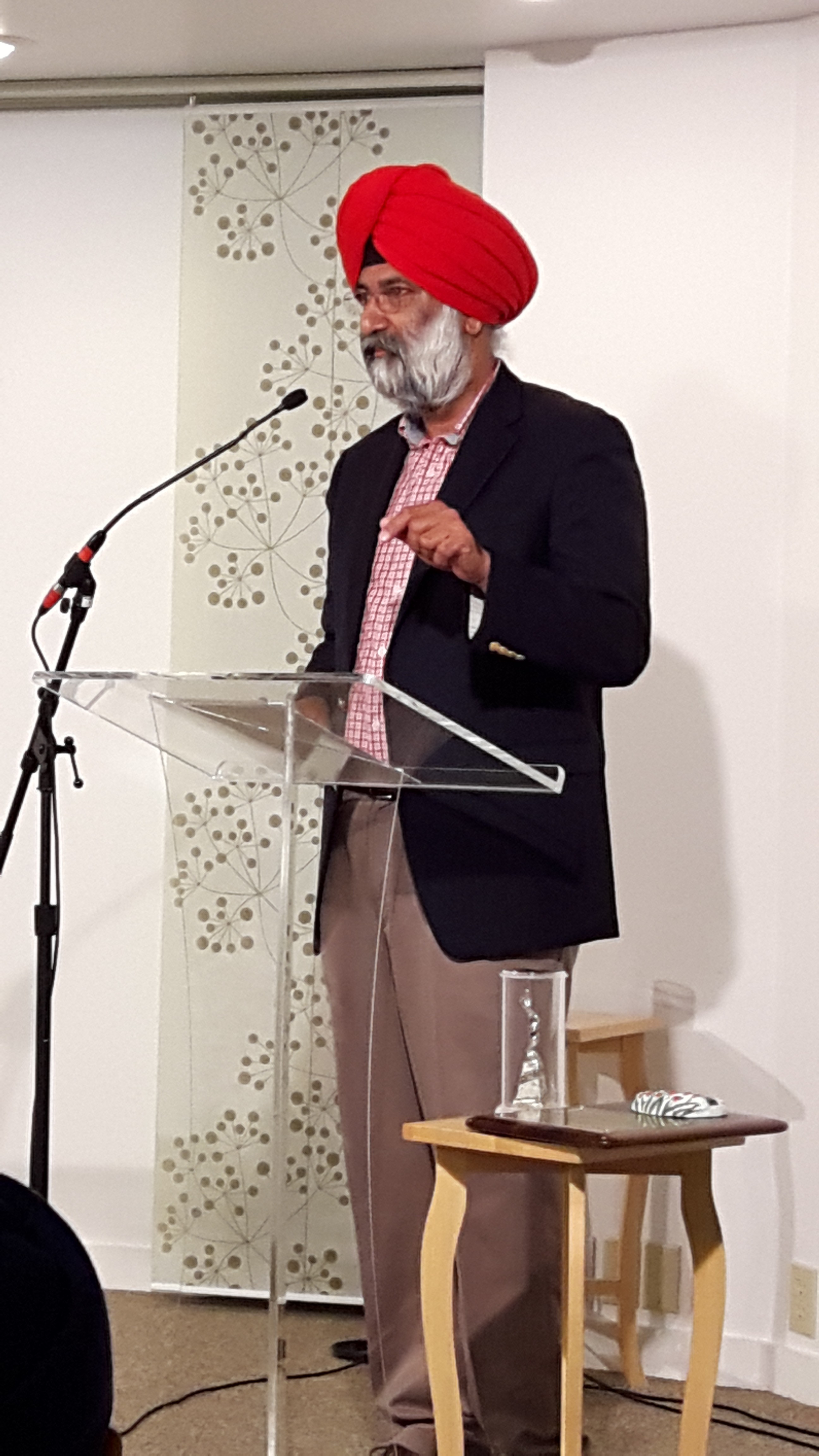

Unity, dialogue, communion – these are words that describe the heart of the mission of the Focolare, and these three words sum up the commitment of Dr Tarunjit Singh Butalia, a scientist at Ohio State University in Columbus, USA. On September 18, 2016 he accepted the 2016 Luminosa Award in Hyde Park, NY. “Your decade-long tireless effort in building bridges on various levels” said Focolare president, Maria Voce, “deserves our admiration and deep appreciation. We feel solidarity and fraternal ties with you and with the Sikh community in the promoting, together with others, peace and care of our common home.” Urged by a strong belief that religions have a crucial role to play in the great work of interreligious dialogue, in 2011 he accepted the invitation of Pope Benedict XVI to participate in the World Day of Prayer for Peace in Assisi. In his acceptance speech the scientist recalled the friendly invitations to interreligious meals and picnics that marked the beginnings of his contacts with the Focolare Movement. A friendship, he explained, that over time developed into trust. He stressed the particular role that religion has always played in American society, precisely because it is a nation of immigrants. While former waves of immigrants seamlessly blended into the people after a few generations, many immigrants from the last 50 years – like Muslims, Buddhists, Sikhs, Hindus, Jains and Baha’i – want to maintain their religious identity. Butalia said “they have made the United States one of the most cosmopolitan countries in the world.” He also observed the importance of acknowledging pluralism as a value “where each part maintains its identity and yet remains part of the harmonious whole.” “We have to focus on building relationships,’ he said; “we need to be able to talk about our differences.”

Unity, dialogue, communion – these are words that describe the heart of the mission of the Focolare, and these three words sum up the commitment of Dr Tarunjit Singh Butalia, a scientist at Ohio State University in Columbus, USA. On September 18, 2016 he accepted the 2016 Luminosa Award in Hyde Park, NY. “Your decade-long tireless effort in building bridges on various levels” said Focolare president, Maria Voce, “deserves our admiration and deep appreciation. We feel solidarity and fraternal ties with you and with the Sikh community in the promoting, together with others, peace and care of our common home.” Urged by a strong belief that religions have a crucial role to play in the great work of interreligious dialogue, in 2011 he accepted the invitation of Pope Benedict XVI to participate in the World Day of Prayer for Peace in Assisi. In his acceptance speech the scientist recalled the friendly invitations to interreligious meals and picnics that marked the beginnings of his contacts with the Focolare Movement. A friendship, he explained, that over time developed into trust. He stressed the particular role that religion has always played in American society, precisely because it is a nation of immigrants. While former waves of immigrants seamlessly blended into the people after a few generations, many immigrants from the last 50 years – like Muslims, Buddhists, Sikhs, Hindus, Jains and Baha’i – want to maintain their religious identity. Butalia said “they have made the United States one of the most cosmopolitan countries in the world.” He also observed the importance of acknowledging pluralism as a value “where each part maintains its identity and yet remains part of the harmonious whole.” “We have to focus on building relationships,’ he said; “we need to be able to talk about our differences.”  Dr Butalia then proposed to take a step further than the Golden Rule (Do to others as you would want them to do to you,” Mt 7:12). He called his version the “Platinum Rule”: “Do to others as they would want you to do to them,” moving beyond the assumption that the other people would like to be treated the way that you would like to be treated yourself.” He then invited the 130 participants to “listen more than we speak” and to never compare the “best of our religion with the worst of the others.” Referring to Islamophobia, Butalia remembered that all religions are interdependent on each other and that we have to stand up against discrimination against any faith. Closing, he quoted a disciple of the Sikh founder Guru Nanak, “No one is my enemy, and no one is a stranger. I get along with all.”

Dr Butalia then proposed to take a step further than the Golden Rule (Do to others as you would want them to do to you,” Mt 7:12). He called his version the “Platinum Rule”: “Do to others as they would want you to do to them,” moving beyond the assumption that the other people would like to be treated the way that you would like to be treated yourself.” He then invited the 130 participants to “listen more than we speak” and to never compare the “best of our religion with the worst of the others.” Referring to Islamophobia, Butalia remembered that all religions are interdependent on each other and that we have to stand up against discrimination against any faith. Closing, he quoted a disciple of the Sikh founder Guru Nanak, “No one is my enemy, and no one is a stranger. I get along with all.”

Dr Tarunjit Butalia with the Sikh delegation

Organized by the Umbria Diocese with the Franciscan family and the St. Egidio Community, the event gathered the religious leaders of the world, and was also attended by cultured men and women and representatives of institutions. Also the Focolare Movement was present in both the preparatory and participation phases, especially the communities in Umbria and in the persons of Rita Moussalem and Roberto Catalano, heads of the Focolare’s interreligious dialogue. With his presence on 20 September, Pope Francis continued the work of John Paul II who had felt the need in 1986 to institute a day of prayer for peace, and had foreseen the role religions could play to avoid conflicts and also contribute to resolving them. In 2011, Benedict XVI had presented peace not only as a commitment of men of faith, but also as a cultural project. But the world is no longer that of the 1980s, the bipolar world of the Cold war. The world is now globalized and multipolar, where the wars have multiplied without ever being wars of religion. Pope Francis greeted each of the leaders personally, starting from a group of refugees who represented the challenges of the world today. It was not only a formal act. There were deep moments of intense bonding that were able to establish important ties for the future. A second moment was the luncheon at the Holy Convent, to which the Pope had invited all to be by his side. Having a meal together under the same roof was in itself an act of peace, after which, a common moment of prayer followed, but not together. Each religion had a facility where members could go to pray for world peace, according to their own religious tradition. Each did so distinctly; this fact aimed to cancel the doubt that these moments were an attempt to amalgamate all religions together. The Christians prayed together to demonstrate that unity among the Churches is fundamental in giving important contribution to peace, as followers of Christ.

Organized by the Umbria Diocese with the Franciscan family and the St. Egidio Community, the event gathered the religious leaders of the world, and was also attended by cultured men and women and representatives of institutions. Also the Focolare Movement was present in both the preparatory and participation phases, especially the communities in Umbria and in the persons of Rita Moussalem and Roberto Catalano, heads of the Focolare’s interreligious dialogue. With his presence on 20 September, Pope Francis continued the work of John Paul II who had felt the need in 1986 to institute a day of prayer for peace, and had foreseen the role religions could play to avoid conflicts and also contribute to resolving them. In 2011, Benedict XVI had presented peace not only as a commitment of men of faith, but also as a cultural project. But the world is no longer that of the 1980s, the bipolar world of the Cold war. The world is now globalized and multipolar, where the wars have multiplied without ever being wars of religion. Pope Francis greeted each of the leaders personally, starting from a group of refugees who represented the challenges of the world today. It was not only a formal act. There were deep moments of intense bonding that were able to establish important ties for the future. A second moment was the luncheon at the Holy Convent, to which the Pope had invited all to be by his side. Having a meal together under the same roof was in itself an act of peace, after which, a common moment of prayer followed, but not together. Each religion had a facility where members could go to pray for world peace, according to their own religious tradition. Each did so distinctly; this fact aimed to cancel the doubt that these moments were an attempt to amalgamate all religions together. The Christians prayed together to demonstrate that unity among the Churches is fundamental in giving important contribution to peace, as followers of Christ.  The concluding ceremony took place in the square in front of the Basilica of St. Francis. The leaders of each religion sat in a semicircle around Pope Francis, as a sign that nobody claimed superiority, notwithstanding the esteem and recognition of the Pope of Rome. His name, his example of a measured life, his words and gestures were constantly cited in the course of the 29 panels or round tables that were held during the prior two days in every corner of Assisi. The conclusion was marked by profound and vital considerations by the Christian, Buddhist and Muslim leaders, and also by moving testimonials: that of a young Syrian mother who arrived in Italy through the humanitarian corridors and that of an elderly Jewish Rabbi, who survived the Nazi concentration camps. The evening was heightened by the speech of Pope Francis who traced a peace roadmap. In fact, «Only peace is holy, not war!» The Pope expressed the meaning of peace by speaking of forgiveness, acceptance, collaboration and education as the fundamental elements to make it possible. «Our future is to live together», he affirmed. It is an idea that universalises the interpretation of the great Bauman who, in the opening ceremony, had underlined how humanity is called today to live the dimension of “we,” and forget the “they.” Once again the framework of Assisi was a decisive element. In fact, peace here is present even in the air we breathe. During these days the Franciscan family offered an example of humble, intelligent and respectful hospitality, constantly at the service of the leaders of the different faiths. It was an evident demonstration of how the humbleness of Francis of Assisi spoke out and asked his followers to make this a fundamental condition for dialogue and peace. It was a sign that peace is built by all of us together, and that each one brings a unique and indispensable gift for the processes of peace. by Roberto Catalano Source: New City

The concluding ceremony took place in the square in front of the Basilica of St. Francis. The leaders of each religion sat in a semicircle around Pope Francis, as a sign that nobody claimed superiority, notwithstanding the esteem and recognition of the Pope of Rome. His name, his example of a measured life, his words and gestures were constantly cited in the course of the 29 panels or round tables that were held during the prior two days in every corner of Assisi. The conclusion was marked by profound and vital considerations by the Christian, Buddhist and Muslim leaders, and also by moving testimonials: that of a young Syrian mother who arrived in Italy through the humanitarian corridors and that of an elderly Jewish Rabbi, who survived the Nazi concentration camps. The evening was heightened by the speech of Pope Francis who traced a peace roadmap. In fact, «Only peace is holy, not war!» The Pope expressed the meaning of peace by speaking of forgiveness, acceptance, collaboration and education as the fundamental elements to make it possible. «Our future is to live together», he affirmed. It is an idea that universalises the interpretation of the great Bauman who, in the opening ceremony, had underlined how humanity is called today to live the dimension of “we,” and forget the “they.” Once again the framework of Assisi was a decisive element. In fact, peace here is present even in the air we breathe. During these days the Franciscan family offered an example of humble, intelligent and respectful hospitality, constantly at the service of the leaders of the different faiths. It was an evident demonstration of how the humbleness of Francis of Assisi spoke out and asked his followers to make this a fundamental condition for dialogue and peace. It was a sign that peace is built by all of us together, and that each one brings a unique and indispensable gift for the processes of peace. by Roberto Catalano Source: New City